By Thomas Munck, Glasgow

Does the extraordinary global public health crisis of 2020 make our next planned Workshop seem distant, even insignificant in the face of existential challenges? Can we learn from the past? There is certainly no shortage of new ideas about what could happen, and what should happen, once governments start relaxing social distancing and protection measures.

Is this an opportunity for more fundamental change? What can we do to tackle some of the huge social and ethnic inequalities that have been thrown into sharper relief? How do we ensure debate is based on reliable data and sustainability? Is democracy itself at risk, and is this an opportunity to remind ourselves that some features of civil society cannot be left to private or market forces, and will always be the responsibility of collective government?

How far is consensus-based government compatible with a reasonable level of individual freedom? How can we re-think social justice, constructive citizenship, political accountability and human rights, while seeking better economic sustainability?

At our 2019 Workshop, we recognised that as historians we might be well placed to understand how an informed public debate has always relied on a good understanding of the processes of communication and dissemination of ideas, as well as on analysis of the ideas themselves and of the political contexts in which they might develop.

In the centuries from the Reformation to the French Revolution, every major crisis was accompanied by surges in print. All forms of printed text (ranging from academic books to pamphlets, and newspapers to fictional speculation) took on a central role as the most effective means of communicating and conducting public debate reliably.

Historians can map this dissemination clearly, but they can also observe how uneven the market was, how some apparently innovative texts in fact did not have much impact when first published, and ultimately how the reception of a text often says a great deal about the nature and cultural assumptions of the society in which it was published. It is now more important than ever to extend such analysis to cross-national communication: which texts were translated into other languages, when and why, and how ideas were adapted or modified in the process.

These were some of the questions that already made our first two workshops, held at the Herzog August Bibliothek in 2018 and 2019, so fruitful. As we wonder whether we may have to postpone the 2020 workshop, or rely more on the internet, we cannot help but be reminded of another question: how far did the medium of communication, and its materiality, affect the message?

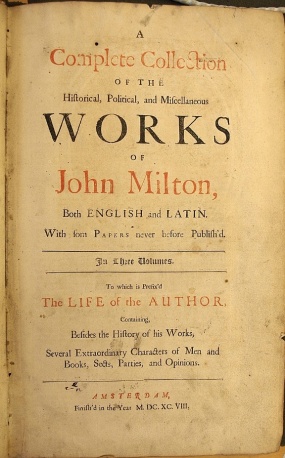

When some of the political works of Milton were reprinted and translated, over a period of 150 years after first publication, were they primarily intended for an elite readership, or also sold more cheaply for a wider audience? Why did Fénelon’s fictional Adventures of Telemachus remain a best-seller across Europe for decades, although written by a French Catholic archbishop?

Why did the pamphlets of Richard Price from the 1770s, responding positively to the American struggle for self-determination, gain a wide readership in French and Dutch, but not in German or the Scandinavian languages? If Moses Mendelssohn was already widely known across Europe for his text on the immortality of the soul, why did his short and wonderfully accessible text on the right of religious freedom not have many readers outside Germany?

I have just come across a substantial serial, launched in 1798 by the French ministry of the interior, aiming to publish French translations of a range of English and German texts on poverty and institutional relief. The series was sustained for a few years, and by 1804 covered 39 issues. It is not difficult to explain why there might have been renewed interest in nation-wide poor relief during those years. But it is interesting to observe that the serial was published in relatively modest octavo format, and often included only extracts from longer works.

So was each issue kept small and priced modestly in order to reach a wide readership, or was it meant for a limited network of officials responsible for the now nationalised poor houses and hospitals? Or was this just a way of drawing attention away from huge social problems and administrative chaos under an unpopular government?

The history of the dissemination and cultural translation of texts is full of such puzzling but fundamental questions. We also need to understand why some texts did not travel well: were censorship systems so impenetrable that publishers did not want to risk losses? Was the first translation inadequate or simply never completed? Did some texts suffer from poor marketing, or were there other barriers?

It is difficult for us to fully understand what early modern readers might have made of what they read. But there is no question that substantive historical investigation of cultural translation can tell us a great deal both about the priorities in public debate in early modern Europe, and about the varied visions of how civil society could function.

tm/gm